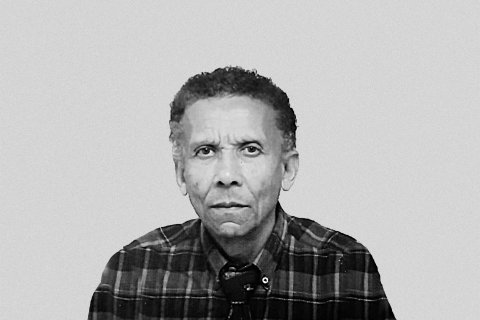

For economist and journalist Carlos Rosado de Carvalho, who described the looting and violence as "reprehensible and unjustified from any perspective," what happened "didn't come out of nowhere."

"They were indeed predictable given the deterioration in Angolans' living conditions... given the social conditions in which they live, and any spark can have consequences and can set off a powder keg," he stressed in a statement to Lusa.

The violent protests coincided with a taxi operators' strike and demonstrations against the rising cost of living called for Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday in the capital.

At least four people died and more than 500 were arrested following the protests that began Monday in Luanda, according to the spokesman for the General Police Command, Mateus Rodrigues.

For his part, political analyst Albino Pikasi, also speaking to Lusa, considered that the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) "has lost control of the situation." The protests "are happening because the Angolan people are starving," he summarized.

In this regard, Carlos Rosado de Carvalho draws attention to economic indicators: "Poverty has increased, unemployment has increased, even for those who are employed, wages are declining any day now, the purchasing power of wages is declining every day, and therefore, all it took was, let's say, an opportunity for this (...) to happen."

"Angola has been getting poorer for about ten years, with growth rates lower than population growth, and therefore, this was (...) predictable," he added.

The economist pointed to available images of the protests that show young people.

"We see from the images that very young people are participating in these events. After all, the youth unemployment rate is over 50%+, but (...), I repeat, these things are reprehensible, they are inexplicable, but they exist. They didn't appear out of nowhere; they are the result of something that was already manifesting itself in Angolan society," he emphasized.

Carlos Rosado de Carvalho finds the lack of police on the streets at the beginning of the strike strange.

"I have some doubts about exactly what's happening and, above all, the reaction of the authorities and law enforcement. I find it strange that there was no one on the streets. The policing apparently wasn't reinforced, as far as we could tell. Now, I don't know if the authorities downplayed the events and the strike. Did they ultimately choose to let things unfold so they could later justify greater repression?" he asked.

"It's very strange that, in fact, initially, people acted without any police supervision, isn't it?" he continued.

Albino Pikasi sees the protests as "an act of public dissatisfaction with the ruling party's governance."

The political analyst pointed out that the minimum wage in Angola is 70,000 kwanzas and asked: "How can an African family, which is usually large, with four, five, six children, live on 68 euros? How is that possible?"

Carlos Rosado de Carvalho believes that the entire process of removing fuel subsidies was and is "poorly done."

"This is being done very poorly. But this is the way forward. There is no other way, because fuel is highly subsidized, energy and water are also highly subsidized, and the budget can't handle it," he emphasized.

What the government should do, he argued, is improve public transportation, for example.

Albino Pikasi advocated for mitigation measures to eliminate the subsidies, but emphasized, above all, the need for dialogue.

"It is absolutely necessary for this to continue. Now, it has to be done differently; it has to be done through dialogue, it has to be done through good communication, it has to be done with transparency. For example, it is said that the government will have saved 700 million euros" by ending the subsidies.

"Now, the government needs to come clean and say exactly how much it saved and where the money went," he concluded.