Today, these acrobatic movements are resurfacing on the outskirts of Luanda where Capoeira Angola practitioners revive what will be the style closest to what would have been "played" at the time by the slaves.

According to scholars, at the origin of Brazilian art, there is a traditional dance of southern Angola, Engolo, practiced in a circle, to the rhythmic sound of songs and batuques, such as Capoeira.

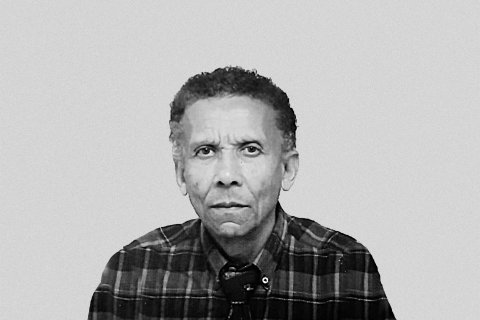

In a hot and muggy room in Viana, a municipality in the province of Luanda, capoeiristas attentively follow the guidance of Mestre João Grande, a world reference of Capoeira Angola who, at the age of 84, still echoes a roaring voice in a song marked by rhythm berimbau.

Slowly, capoeiristas begin to “play”, always “down”, as determined by the rules of Capoeira Angola, which keeps practitioners close to the ground, unlike the aerial acrobatics and quick strokes that characterize Capoeira Regional, created in Bahia.

“Capoeira Angola comes from below, it's like a plant that grows”, explains João Grande, who was a disciple of Mestre Pastinha, the main promoter and promoter of this style, and is in Luanda to participate in the 1st Capoeira Angola Festival, which ended this Monday.

“Capoeira is my life”, he proclaims, telling that he started practicing the sport in 1950 with Mestre Pastinha who, in turn, learned it from an Angolan.

“Before he died, he said: Capoeira Angola is here in Brazil and will return to Angola again. Capoeira de Angola is the seed and can never die”, says Mestre, who continues to transmit his knowledge to students from all over the world.

He ensures that the practice is accessible to anyone: “It is for everyone, it is for men, boys and women. It just doesn't learn who doesn't want to”.

An art that was born as a dance, but was in reality “a fight to beat the boss”, with music helping in disguise, he says.

“The slaves took it as a dance and then it became capoeira. They did dance and when the inspector arrived, they said: 'we are playing here, doing a dance', he reports.

That is why, like agile movements, the music of “drums”, the group of berimbau players and percussions of the Capoeira roda, is inseparable from this practice, highlights João Grande.

“Music is the joy of Capoeira. Singing gives strength and joy to the player and those who are enjoying it. It is like the little bird that singing cheers others up”.

And it is the capoeiristas who make their own instruments.

Mário Epalanga, professor of the Uavala group and practitioner of Capoeira Angola, shows how to make a berimbau.

“Nothing here is from another part of the world, but from Africa. We have a gourd, which in the past was used to store food and conserve fresh water, and we have a wire here. What we use is a tire”, he describes, striking the wire with the wooden stick.

The lintel, which "we take out of the forest", joins the two ends of the wire, similar to an arc and completes the instrument.

In the other hand, he holds a handmade “caxixi”, a kind of rattle made of a straw plait with seeds inside, which adds rhythm to the drums.

It presents Capoeira Angola as “a dance that brings a lot of art together”, a game “made on the ground, with a lot of mandingo [trick], a lot of softness [swing]” and “many strong connections” to Angola.

The studies that have been developed reveal that there are many similarities between Capoeira and Swallow, so that Brazilian art was a “development of what already existed”.

“Fortunately, he is back in Angola”, smiles the professor.

In addition to "a lot of interconnection in movements", Engolo also has drums like Capoeira "has palms, has singing" and, above all, "has to have a lot of energy".

It is this “foundation, this culture and tradition” that Capoeira Angola practitioners want to rescue.

But talking about Capoeira is not just talking about movement and drums, Epalanga continues. It is talking about the stories of the past because "many of our ancestors went from here to Brazil", he recalls, pointing out that "Capoeira was a fighting mechanism for many people". In an environment of oppression, “the slave found refuge in capoeira”, emphasizes Epalanga, for whom “Capoeira helped a lot in the liberation of the black people” and served to fight against repression”.

Art was banned until the 1930s, even after the abolition of slavery in 1888. “Today, thanks to God, it is already a world heritage site”, the capoeirista congratulates, noting that the practice is also increasing in Angola.

Mateus Sobrinho, 16, is one of the youngsters who follows, silent and focused, the “game” of the most experienced, while waiting for his turn to enter the roda.

It started in November, but “since I was a child” who enjoyed art particularly attracted “by the ginga and the sound of the berimbau”. Learning "is not difficult", but it takes a lot of practice, he admits.

Mateus is just one of thousands of practitioners of this art born in Brazil, currently spread around the world, who helped to face the violence of slavery and survives today,